A critical need for business managers is to be able to pick a talented and trained person and plug them seamlessly into a new project, market, or role. On one hand, this requires deep insights into what capabilities, skills, and talents are required to deliver in a given context, and on the other side, ensuring a supply of such talent.

So, what does it take to create a 'ready talent supply'? It's a tough challenge given a host of variables, each one not always very easily measurable. For example, the mindset of any talented individual at a point in time to move into a new, fairly undefined role, and what it would take to make the move happen.

“Mathematically, an ‘organized complexity’ can be viewed as a set of objects or events whose description involves many variables, among which there are strong mutual interdependencies. As a result, the system of equations that arises cannot be solved ‘piece-meal’…”

It is therefore important to understand and appreciate the variables that have an impact on each sub-system in the talent management chain, as well as how they interplay, creating complexity.

There are both logical aspects that can be easily measured, e.g., pay, job titles, and role aspects (although this is debatable). The more complex variables are psychological and social in nature, e.g., the quality of a new manager or how large an impact the success of the previous role holder has on the new candidate who may be considering a specific role.

HR and line leaders, and even role aspirants, often tend to take a narrow view of the variables. This can lead to frustration on the part of the hiring manager and organization, and often directly impacts employee engagement and retention.

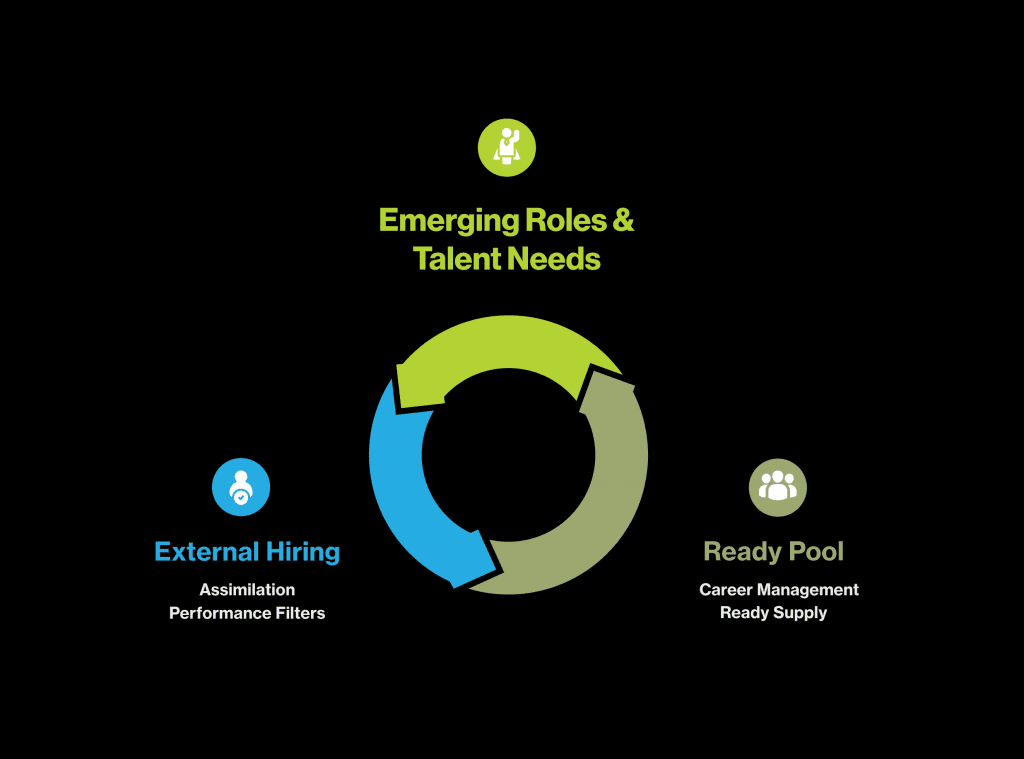

In the context of Talent Management, a simplistic view of the supply chain would look something like this:

Let’s apply the factors of the theory of constraints to examine where efforts may pay off best.

Except for roles where internal capability may not exist at all, there is likely to be better control over skill monitoring and continuous upgradation when managed internally. There is a belief that we may sometimes get better talent from outside, but that has more often than not proven futile. Companies that have invested in internal talent development reap the benefits of stability and a strong leadership pipeline.

But developing quality talent in-house requires:

There is a large pool of people available outside, and often, hiring is seen as an answer to building capacity and capability. It’s useful to ask a few questions, though:

This is the simplest one. In general, the cost of hiring from outside, including various hidden and underlying costs, is significantly higher than developing internal candidates for most positions. Having said that, compromising on an internal, suboptimal candidate may well prove costly in the long run, not to mention opportunity costs.

Interestingly, most HR resources, including financial budgets, are allocated to the recruiting area. This is because costs are more easily identifiable, and the activity related to recruiting is more visible, i.e., “I spent X amount to hire for two positions within three months.”

Development costs on internal resources are less easily measurable and trackable from an immediate impact point of view. Mature leaders tend to take a ‘leap of faith’ on development costs and efforts and are more often than not proven right, although it shows up over a period of time.

Building a talent pipeline internally is often considered too slow and effort-intensive. Contrast that with trying to build it by focusing on talent from the outside. The time, effort, and lack of clear outcomes will be deterrents. While sometimes moving an internal person to a new position or role can take time, it is a far more in-control process and with a clearer view of outcomes. Expectations from the candidate can be better calibrated.

A completely new outside hire is a bit of a punt and may take a long time to find, with no guarantee of success. In these times, with last-minute candidate backouts, time periods could get extended significantly.

All in all, there is a strong case for investing in assessing and developing internal talent in order to have a more ‘ready’ pipeline.

One of the key challenges for HR is to have a really good view of every single employee beyond just skills: aspirations, career plans, and needs at any given point in time, etc. This 'knowledge' will aid candidate mobility and skill transfers, as well as bring a real understanding of the depth of the talent pool.

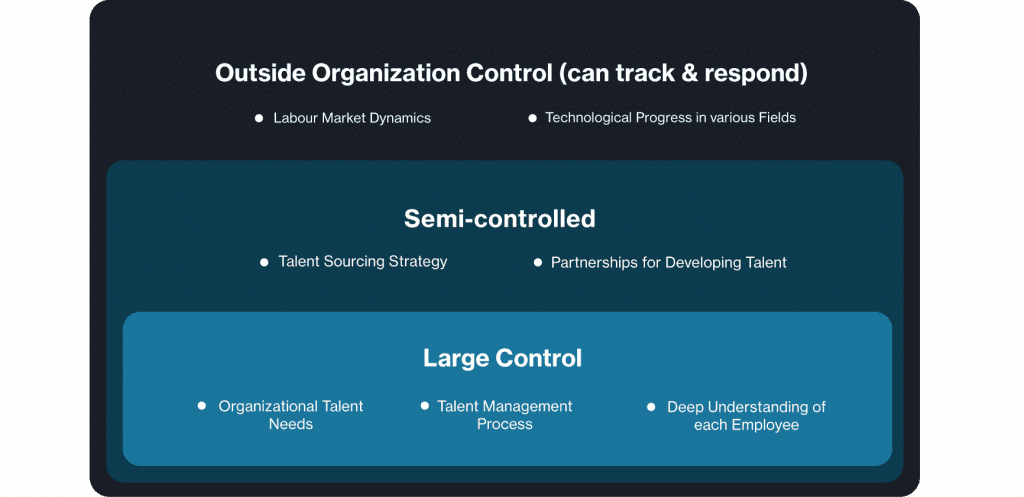

If we apply another filter to distinguish what is controllable or not controllable by the organization, a clear case for investing in internal talent emerges. All internal processes—assessment, specific training on a skill, peer and superior feedback gathering, etc.—are more manageable and can be executed with speed. Labor market dynamics, external candidate behavior, past performance information, etc., are likely to be less within any organization’s control. Again, this makes a strong case for investing even further in strengthening the internal processes and, consequently, the outcome.

It is a very difficult task to create a strong base with a focus on primarily acquiring talent from the outside all the time. The costs, including hidden and opportunity costs, point clearly to investing in internal talent being preferable to hiring all the time—except, perhaps, in very specialized areas. To bring increased certainty in talent availability and link to expected performance, investments in internal talent may again yield better results

In summary, it is imperative to keep parameters such as cost, time, quality, quantity, and variable control in mind while focusing on internal processes to build a robust talent base. This base then serves as the launch pad for talent mobility in an agile fashion.

Regular and robust talent reviews, formal assessments that consider the future requirements of the organization, and transparent communication of talent information to senior leaders are key actions needed to support agility in the talent movement.

Going back to the concept of organized complexity, every piece in this puzzle will need to be dealt with individually and yet collectively.

Here is one way to look at these ‘parts’ and plan for action in one’s own organizational context:

info@thinktalentindia.com

+91-9910955257

+91-8828158509